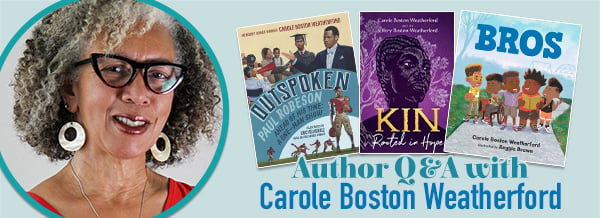

Author Q & A with Carole Boston Weatherford

“Poet. Mother. Daughter. Oh, and creative!”

Those were the three—well, four—words that Carole Boston Weatherford used to describe herself when prompted.

As a writer and fulltime professor with over 80 authored titles, Boston Weatherford writes for all different audiences including young, middle, high, and adult poetry readers—so there truly is something for everyone! Her books written in verse constitute a rhythmic flow and the economy of her words ensure that readers are getting to “the heart” or “the essence” of what characters are truly trying to say, all with a little help from Boston Weatherford’s ancestors.

Take ten minutes out of your day to learn more about how Boston Weatherford and her artistically talented son, Jeffery Boston Weatherford, collaborate and co-author projects, the advice she has for Black students experiencing erasure in their histories, and how critical fabulation can help strengthen librarian’s curation efforts. Ultimately, you’ll learn of Boston Weatherford’s dedication to the African American experience and her anti-racist writing that explores a balance of empathy and activism:

“I don’t think there needs to be that dichotomy or tension between writing about Black trauma or joy—they are both very real and we don’t have to choose one or the other. The tension is real; we carry it within us. We have a right to joy, but we also need justice, which means being true to our pasts and exposing injustices.”

Q: Carole, you have authored over 70 books! When did you first fall in love with storytelling? Have you always aspired to be an author?

I've been in love with storytelling all my life. I grew up in a language rich environment that included not only books but also oral traditions like the stories that my mother, grandmother, and father passed down, and the Black preaching tradition that I experienced in church. My grandfather was a preacher. Unfortunately, I never heard him preach, but nevertheless, I was steeped in those traditions. My grandmothers spouted proverbs, told stories, and made quilts (which can also be narrative in a way). I was always in love with the stories and by the time I started school and fell in love with the school librarian—who had this mellifluous voice! —I was more than ready to sit, listen, and learn to read. I can remember hearing the librarian tell African folktales and introduce new books to the class. There weren't many books that had African American characters at that time. But that did not dull my enthusiasm or dim my light—I had no clue that books were supposed to have African American characters back then because I didn’t see us in the media either, besides Ebony Magazine. I didn’t realize that I was supposed to be represented in books. There’s no telling who I'd be now had I seen myself represented in books as a child.

I composed my first poem in first grade, dictating it to my mom on the way home from school. She parked the car because she was so surprised and asked me if I could recite it again. When I said it the second time, she wrote it down. She had parked the car when we were only two blocks from home, so she knew it was important to stop and capture that poem. I dictated the poem to my mom. It turned out that I was not a one-hit wonder. As I made-up more poems in the early grades, my mother asked my father to print some of my poems on the printing press in his classroom (both my parents were educators). He used my poems as typesetting exercises for his students, which meant that I got to see my work in-print at a very early age, before the dawn of any of the digital technology that we have today. My poems were printed on letterpress on index card sized, cardstock. I gave some to my friends. My mom kept those poem cards in her dresser drawer for over three decades, and I still have a few of them.

I did not dream of being a poet, even though I was writing poetry all through elementary, junior high, high school, and college—I was even a creative writing minor in college! Becoming a writer was not considered a practical career in my culture and community; I didn't know anybody who was making a living that way when I was growing up. Even though I was devouring library books as a girl, I assumed that the authors were dead—there was a disconnect. I also had no clue that the people who were writing the books were getting paid! I didn't have a role model for a literary career, but I did know about journalism, so after college, I wound up in public relations and really enjoyed it. My news stories were my first publication credits.

I did not meet a real-life author or attend poetry readings until I was a young adult in college. I saw now legendary poets of the Black Arts Movement reading their poetry aloud. When I saw Ntozake Shange’s play, FOR COLORED GIRLS WHO HAVE CONSIDERED SUICIDE/WHEN THE RAINBOW IS ENUF, it dawned on me that poetry had a home not only on the page but could also be performed on the stage.

When I was 24, something happened that changed my life: I had a poem published in a magazine. It was a poem much like the first poem that I wrote, and it was called “I’m Made of Jazz”. The idea, the words, the rhythm—it all came to me in a piece out of the blue. At the time, I was headed to graduate school on a fellowship to study public administration. I had decided to pursue this degree because I couldn’t find a job in two public relations because:

1. We were in the middle of a recession.

2. I am African American.

I was bound for graduate school—on a full ride—and then the summer before I left, my poem about jazz was published. I began telling people I was a poet, and I started believing that I could get a book published someday. At age 24, I envisioned poet-ing as my life’s work. I went to only one class session on that fellowship and then I dropped out of graduate school. Later, I ended up paying my own way through graduate school not once, but twice. I obtained a degree in publications design and then 10 years later, an MFA in creative writing. I was writing poetry for adults then and was published in literary journals.

When I became a mother in my thirties, I aimed to raise my kids in a language-rich environment, so we read books and went to library story times. At the library and bookstores, I was exposed to a whole new crop of children's books, one that was more diverse than the selection that I had access to as a kid. I welcomed the diversity and it dawned on me that perhaps I could write for children. I had already written a few rhymes for my kids—just to entertain them, not to be published. While I was submitting manuscripts for adult poetry, a light bulb went off in my head. In particular, I remember how much my kids loved the book Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold at that time. I thought, “Well, maybe I could write for children.” Ringgold’s concept was imaginative, the art was brilliant. From that point on, whenever I took my kids to story time, I was in the nonfiction section borrowing books about writing or children’s book publishing. I was always borrowing children's books from the library and from my children’s collections to study as mentor texts.

I have a feeling I've lost count, but I think the number books I have written is in the 80’s now… or at least it will be by the end of this year! I’m a full-time professor at Fayetteville State University in North Carolina and I've been doing that for 22 years. I get asked all the time if I sleep. I sleep every night for about, oh, 5 hours…

*chuckles*

I always prioritize my writing because that is what brought me to “the party” in terms of academia. When I became a professor in 2002, I had 6 books published. I’ve continued to write because writing is not what I do, it's who I am. I became more focused on my career as a children's book author after the publication of my first book, Juneteenth Jamboree, in 1995, although I did not have the luxury of being a full-time author at that time. As the years passed, I devoted more and more of my time to my literary career.

As a professor, I’ve taught children's literature, adolescent literature, creative writing, and business and professional writing, and I created a new course called Hip Hop Poetry, Politics and Pop Culture. I thought it was important for a HBCU to have a Hip Hop course. There are Hip Hop courses at Harvard, MIT, lots of colleges, and it’s been around for 50 years… Hip Hop is here to stay.

Q:Tell us more about the creative partnership between you and your son! Which elements come first, the writing or the illustrations? What has been your favorite project to collaborate on?

When my son Jeffery was born and my mother first held him, she said, “Oh, he has large hands! He's going to do important work with his hands.” We all thought that meant he was going to be a neurosurgeon—a neurosurgeon! It became evident however that Jeffery’s gift was for creating art. He focused on art in high school, majored in art in college, and received his MFA. For his senior project in high school, he illustrated one of my manuscripts. In a college internship, he shadowed illustrator Jim Young, a children’s book illustrator and librarian from North Carolina. Jeffery illustrated a manuscript with digital collage. That project would become You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen.

Jeffery and I received a contract from a publisher for that book, but later the press was acquired, and the contract was killed. Before we pitched the project again, I asked Jeffery, “Why don’t you try illustrating this with scratch board?” which he had practiced in college and high school. So, he re-illustrated the book, we submitted it again, and we got the contract! That’s how Jeffery’s career started. His debut picture book was Call Me Miss Hamilton (another collaboration), and then we worked on our third book, KIN: Rooted in Hope.

When we work together, I do a lot of picture research for my own writing process. I share my findings with Jeffery—probably too much…I probably overwhelm him… but I think we work very well together. We used to live together. Now, our creative process because I’m in Baltimore and he’s in Charlotte. I don’t necessarily see all his sketches as he’s making them, but rather as a batch when he sends them to our editor and art director—unless he’s extremely excited about a piece that he’s working on, then he might share it with me sooner. Sometimes, I try to conceive projects with my son in mind and he does the same for me. We not only collaborate as author and illustrator, but as co-authors. We have two books that we are working on right now and one is about how to write rap lyrics. We’re really excited about this book which grew out of the Hip Hop Tech workshops that Jeffery leads. He’s a poet and a rapper. The text focuses on lyricism and rhythm—it is really fun! Rap it Up will be released in March 2025.

Q: What power or unique elements does poetry bring to your storytelling?

It's the process of cutting things out to get to the heart of the story—getting to the essence of what that character might want to convey—and then I try to boil down their messages and condense their stories into poetry. In the case of KIN, I conjure my ancestors. I asked them to speak to and through me. I do as much research as I can. However, with African American history, you hit a lot of brick walls: our history was not documented well because it was not deemed important enough by those in power.

A few weeks ago, during an SLJ webinar, I spoke about critical fabulation. That term was coined by Saidiya Hartman who is a MacArthur Genius Grant recipient and a professor at Columbia University. She contends that archives can only take us so far—especially in documenting enslavement—so it’s up to use imagination to shape the facts into a story. Critical fabulation encourages the writer to use creative license to reclaim lost narratives. That’s what I tried to do in KIN and many other of my books. My mission is to mine the past for family stories, fading traditions, and forgotten struggles that center on African American resistance, resilience, remarkability, rejoicing and remembrance.

I have no qualms about pushing past the archive and speculating. I’ve been told that my work is also Afrofuturist because I recreate ancestral voices. This process connects me with my ancestors. I want to carry that wisdom forward. I like to write about historical subjects because history informs the future.

Q: A few weeks ago, you participated in SLJ’s webcast, “Fact Finding and Black History” and cited the term, “critical fabulation”. What advice would you offer to librarians and their curation efforts in the context of “critical fabulation”?

When books push past the limits of the archive, that doesn’t make them any less credible, in fact, I think the value is enhanced because the books uncover lost narratives. For too long, Black voices have been marginalized and our history was dismissed and devalued. There’s a place for fact finding and reporting, a place for narrative nonfiction, for creative nonfiction and for critical fabulation. When librarians go to curate these books, I hope they embrace the fact these books may defy categorization. Some librarians don’t know where to shelve my books, and sometimes reviewers don’t get them either. My book KIN, for example, is a verse novel—merging poetry and historical fiction. But Kin is also informational.

Q: KIN: Rooted in Hope follows the histories of your enslaved ancestors, giving a voice to those who have been seemingly erased from history. After your research and fact-finding, what questions do you still have about your lineage? Were there other people or histories you were hoping to learn more about?

If your readers are having a hard time researching their genealogy due to Black or minority erasure, what advice what you offer them? What next steps can they take?

I would really like to know when my ancestors came over and learn more about my African origins—more than the archive or DNA tests have been able to tell me. The earliest account of my ancestors is in 1770 at a plantation on Maryland’s eastern shore. Before the Revolutionary War, my family was here in the colonies, but I don’t know if they were born in Maryland or if they came over from Africa or the Caribbean. However, I got wind of local lore that my great, great, grandfather was known as the “Royal Black” because he could trace his ancestry to African royalty. But to what tribe? I don’t know—I never met the man, just found a picture of him in the process of researching KIN. I had never even seen his face until I researched the book, and that was one of the biggest takeaways—seeing his face and discovering that I may have royal blood.

I would have loved to know an exact location, date, and ship that my ancestors came over on, but I was only able to narrow it down to about 30 different ships. There are several questions poems in KIN that that seek answers. Question poems are my way of grappling with the unknown.

I could not imagine working on KIN with anybody other than my son—it really was quite the journey. Even before conceiving the project, we went to West Africa—not for research purposes, but to present at international schools. The whole time we were there, I kept wondering, is this the nation, the region where my ancestors came from? In Senegal, Ghana, and Cote d'Ivoire, I kept expecting to feel the pull of my ancestors telling me, “This is where you are from. This is the soil where your ancestors walked”.

My advice to those seeking to learn more about their histories is to learn all you can—seek out the information, because it will empower you. It’s not going to fall in your lap, and you can’t expect teachers to give it to you. Yes, our educators are doing more than they used to in the field of Black History, but you can’t expect to learn solely from the curriculum. You might get some information, but you need to go beyond that and talk to your family about your history or African history in general.

For me, the major takeaway from KIN is that knowing your history is generation wealth. Due to historic discrimination, African Americans have less generational wealth to pass on. That inequity is one reason some leaders are pressing for reparations. Generational wealth usually means money, property and other material goods that can be left to heirs. However, the foundation of generational wealth is not money, but knowing where you came from—if you don’t know your origin story (even if it only goes back two generations), then you’re bankrupt in terms of your identity. You’re empty inside. The fact that African American history is under siege suggests how powerful and transformative that knowledge can be. In the wake of book bans, we must teach African American history in the community, and that means through churches, businesses, beauty salons, barber shops, youth organizations and the like. Our history has been omitted and we can’t wait for others to give it to us. We must seek it for ourselves, and the library is a good place to start that journey.

Q: Outspoken: Paul Robeson Ahead of His Time is a unique, poetic biography about a lifetime advocate for racial injustice. Robeson is a talented individual, excelling in sports, law, performance arts, and politics—just to name a few areas of his talents! How did you first learn about Robeson’s life and what compelled you to write his story?

It was James Earl Jones who led me to Paul Robeson. My dad took me to a play about Paul Robeson, a one-man show starring Jones. I knew very little about Paul Robeson when I went to see that play as a young adult. Paul Robeson impressed me as a heroic figure in African American history.

Robeson sacrificed everything for the freedom struggle and the labor movement. He had communist leanings and thus was blacklisted during the Red Scare. His career never bounced back. Like some of my other biographical subjects, Paul Robeson has fallen into obscurity, at least among young people. I wanted to spotlight his exceptionalism and his activism.

Q: In the poem titled “Rockin’ Chair”, you pose the question, “What will history write of [Paul Robeson]?” and go on to list numerous attributes about Robeson like activist, hero, musician, scholar, artist, brother, leader, etc. What do you hope history writes about you and what attributes would be included on your list? Do any of your attributes match Robeson’s?

Paul Robeson and I probably share a few attributes… people probably don’t know this, but I played football, basketball…

*chuckles*

I’m just kidding, I didn’t play those sports, but I’d like to think that there are attributes I share with Paul. For my part, I contribute to the freedom struggle by empowering young children with their history. I would like to be remembered as a poet, mother, and a race woman—I am for my people. My Blackness informs all I say and do. I’d like to be considered gifted, conscientious, African American, powerful, an artist, a reader, a Renaissance woman… In addition to writing books, I’ve designed clothes, I’m a good cook and sometimes I paint. While I’m not a preacher’s son like Paul, I have been a preacher’s wife and a preacher’s granddaughter. I try to act in good conscience, to be an activist, and to be a good citizen.

If I could only choose 3 adjectives to be remembered by, it would probably poet, mother, and daughter—and creative. Okay, so four words.

Q: Bros is a lyrical picture book filled with energetic illustrations and rhythmic text. How did the #BlackBoyJoy meme inspire this book? What do you hope young readers take away from this story of joy, light-heartedness, and Black representation?

I wanted to create this snappy little poem—around 52 words total. For this book, I wanted to play with language, and I wanted to talk to black males. From boyhood to manhood, Black males carry a heavy burden in American society. I can remember when my son was 11 years old and he and his best friend—I called him my other son—were getting taller. I remember dropping them off at the mall once and saying, “Okay, now, how you act in there because people will view you as adults, and they’re going to discipline you as adults. You can’t be running around acting silly.” That’s a lot of pressure on a young person to navigate the color line and to face adultification.

After Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice were murdered, my agent urged me to write the book, In Your Hands, which is a Black mother’s prayer for her sons. That is serious, a meditation. While I loved that book, I really wanted to write a book that was fun—Bros—and it probably has something to do with the fact that I’m a grandmother now! Bros is an affirmation of Black boys—to be children, to be boys, to be young, to be carefree.

Q: Are you working on any new and exciting projects…?

Let’s see… this year I have 7 or 8 books coming out. Bros is one of them, Crowning Glory, —a celebration of Black girl’s hair—comes out in September, a verse biography of Mavis Staples, the gospel and rhythm and blues singer is another one, and I have one about folk artist Vollis Simpson, who created the official folk art of North Carolina called the Whirligigs .

The two projects that I’m most excited about are a poetic biography of Toni Morrison entitled A Crown of Stories—this might be one of my best works of writing!—and The Doll Test: Choosing Equality—which focuses on the study cited in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school segregation case. A Crown of Stories is meant for young people, but it’s really a love letter to Toni Morrison; that book comes out in April 2024 with HarperCollins. The Doll Test documents the doll tests that studied the psychological effects of segregation on African American children. I tell this history from the perspectives of the dolls, who narrate the story. I hope it resonates with young people that same way that How Do You Spell Unfair? does.

Q: How can readers and librarians connect with you?

Often, I do appearances with my son and collaborator. Like I said before, he is not only an illustrator, but a rapper who is quite dynamic and—if I might say so myself—very handsome. We enjoy doing visits together and it’s a great chance for me to see him because we live in different states now.

If educators and librarians are interested in getting in touch with me, click below to visit my website or follow me on the following social media channels:

You can view and add Carole Boston Weatherford's 15 JLG Gold Standard Selections to your Monthly Book Box here: Carole Boston Weatherford books from JLG