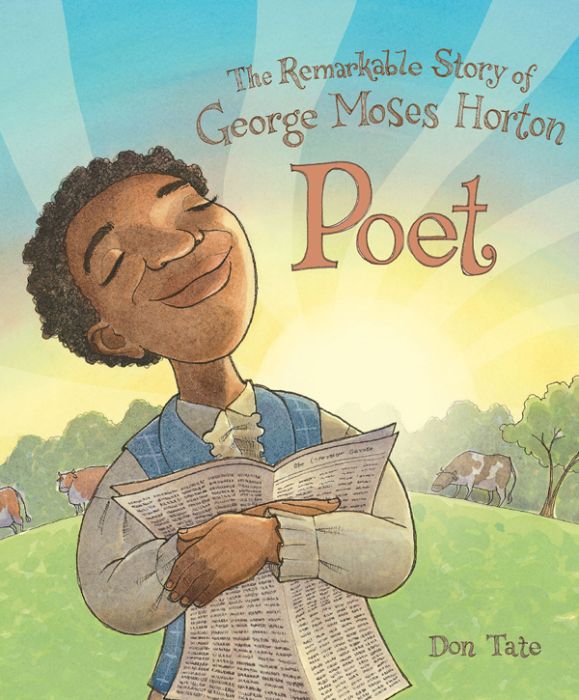

Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton

By Don Tate

Edition

Capitol Choices 2016

Kirkus Reviews Best Children’s Books of 2015, Picture Books

NCSS Carter G. Woodson Book Award 2016 Winner, Elementary ALA Notable Books for Children 2016, Middle Readers

Chicago Public Library Best Books of 2015, Informational Books for Younger Readers

2016 Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People, 3–5

2016 CCBC Choices–Biography and Autobiography

2015 Cybils Awards Nomination, Elementary / Middle Grade Nonfiction

Best Multicultural Books of 2015

2016 Christopher Award, Ages 6 & up

2016 Crystal Kite Award Winner, Texas/Oklahoma

Triple Crown National Book Award 2016-2017

Children’s Literature Assembly, 2016 Notable Children’s Books in the English Language Arts

Children’s Book Committee Bank Street College of Education Best Children’s Books of 2016, Biography and Memoir

William Allen White Children’s Book Awards 2017–2018 Master List, Grades 3–5

By Don Tate

Hardcover edition

Publisher Peachtree Publishers Imprint Peachtree ISBN9781561458257

Awards and Honors 2016 Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award WinnerCapitol Choices 2016

Kirkus Reviews Best Children’s Books of 2015, Picture Books

NCSS Carter G. Woodson Book Award 2016 Winner, Elementary ALA Notable Books for Children 2016, Middle Readers

Chicago Public Library Best Books of 2015, Informational Books for Younger Readers

2016 Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People, 3–5

2016 CCBC Choices–Biography and Autobiography

2015 Cybils Awards Nomination, Elementary / Middle Grade Nonfiction

Best Multicultural Books of 2015

2016 Christopher Award, Ages 6 & up

2016 Crystal Kite Award Winner, Texas/Oklahoma

Triple Crown National Book Award 2016-2017

Children’s Literature Assembly, 2016 Notable Children’s Books in the English Language Arts

Children’s Book Committee Bank Street College of Education Best Children’s Books of 2016, Biography and Memoir

William Allen White Children’s Book Awards 2017–2018 Master List, Grades 3–5

Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton

5

5

Out of stock

SKU

9781561458257J

2016 Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award Winner

As a boy, George Moses Horton taught himself to read, and “words loosened the chains of bondage.” During six decades of enslavement, he became a poet and the first African American published in the South. Bibliography. Author’s note. Full-color mixed-media illustrations were done in gouache, archival ink, pencil, and digitally.

As a boy, George Moses Horton taught himself to read, and “words loosened the chains of bondage.” During six decades of enslavement, he became a poet and the first African American published in the South. Bibliography. Author’s note. Full-color mixed-media illustrations were done in gouache, archival ink, pencil, and digitally.

|

Standard MARC Records Cover Art |

Arts Elementary Plus (Grades 2-6)

Arts Elementary Plus

Arts Elementary Plus (Grades 2-6)

For Grades 2-6

Draw! Dance! Sing! The 14 books in this category celebrate creativity and will foster a love of the arts among elementary schoolers.

14 books per Year

$0.00 per Year

Interests

Biographies, Diversity, Nonfiction, Science/STEAM