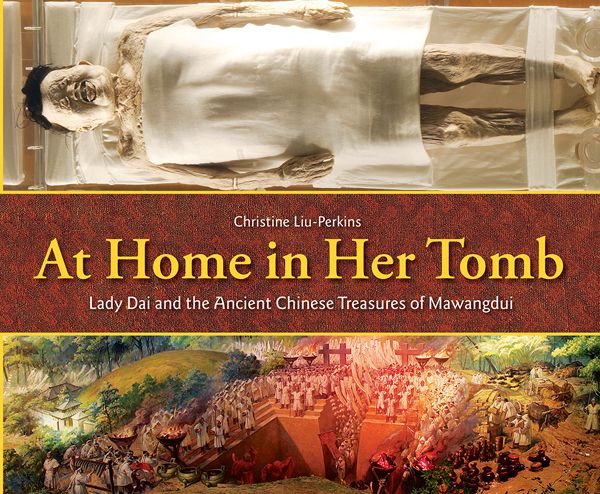

At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui

By Christine Liu-Perkins

Illustrators

Illustrated by Sarah S. Brannen

Edition

By Christine Liu-Perkins

Hardcover edition

Publisher Charlesbridge Imprint Charlesbridge ISBN9781580893701

Awards and Honors Kirkus Reviews Best Books of 2014, Middle-Grade Books; Booklist Editors’ Choice 2014, Nonfiction, Middle Readers; Booklist Lasting Connections 2014, Social Studies; New York Public Library, 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing 2014, Nonfiction; NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K–12: 2015At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui

5

5

Out of stock

SKU

9781580893701J

China: Over two thousand years ago, Lady Dai was buried with her family. In 1972, their tombs were discovered, and Lady Dai’s body was remarkably preserved. Time line of the Qin and early Han dynasties. Glossary. Author’s note. Index. Full-color photographs and watercolor illustrations.

|

Standard MARC Records Cover Art |

Nonfiction Middle Grades 5-8)

Nonfiction Middle

Nonfiction Middle Grades 5-8)

For Grades 5-8

Knowledge is power, and this category embodies that principle. Featuring 12 carefully selected nonfiction books, the collection spans autobiographies, anthropological studies, and more—making it perfect for research, classroom enrichment, and independent exploration. Some selections may explore identity, relationships, and real-world challenges, including LGBTQIA+ themes, moderate language, social issues, and other sensitive topics.

12 books per Year

$256.56 per Year

Interests

Biographies, History, Nonfiction, Science/STEAM