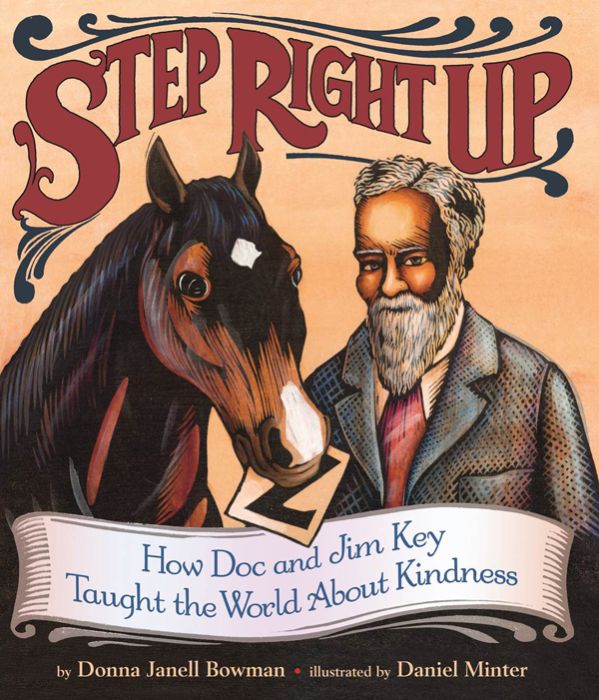

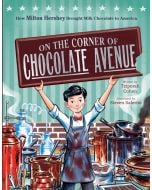

Step Right Up: How Doc and Jim Key Taught the World About Kindness

By Donna Janell Bowman

Illustrators

Illustrated by Daniel Minter

Edition

2018—2019 Prairie Pasque Book Award Winner

NCTE Orbis Pictus Award 2017, Rcommended Book

Booklist 2016 Editors’ Choice, Books for Youth, Middle Readers, Nonfiction

ALSC Notable Children’s Books 2017, Middle Readers

2016 Cybils Finalist, Elementary/Juvenile Nonfiction

By Donna Janell Bowman

Hardcover edition

Publisher Lee & Low Books Imprint Lee & Low ISBN9781620141489

Awards and Honors Beehive Award 2019 Nominee2018—2019 Prairie Pasque Book Award Winner

NCTE Orbis Pictus Award 2017, Rcommended Book

Booklist 2016 Editors’ Choice, Books for Youth, Middle Readers, Nonfiction

ALSC Notable Children’s Books 2017, Middle Readers

2016 Cybils Finalist, Elementary/Juvenile Nonfiction

Step Right Up: How Doc and Jim Key Taught the World About Kindness

12

12

Out of stock

SKU

9781620141489J

A biography of William “Doc” Key, a former slave and self-trained veterinarian, who taught his horse to read, write, and do math. Afterword, with photographs of Doc and Jim Key. Quotation sources. Author’s sources. Full-color illustrations rendered as linoleum block prints painted with acrylic.

|

Standard MARC Records Cover Art |

Biography Elementary Plus (Grades 1-4)

Biography Elementary Plus

Biography Elementary Plus (Grades 1-4)

For Grades 1-4

This 14 book collections offers beginning readers fascinating biographies and compelling personal stories that provide a view into history or perspective on the issues of our times.

14 books per Year

$282.52 per Year

Interests

Biographies, Nonfiction, Science/STEAM